Acervo, Rio de Janeiro, v. 36, n. 2, May/Aug. 2023

Marc Ferrez: the photography as an experience | Thematic dossier

Landscapes in transit

The Carioca landscape historicity and appropriations

Paisajes en tránsito: historicidad y apropiaciones del paisaje carioca / Paisagens em trânsito: historicidade e apropriações da paisagem carioca

Maria Inez Turazzi

PhD in Architecture and Urbanism from the University of São Paulo (USP). Senior research fellow at the Laboratory of Oral History and Image at the Institute of History of the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), Brazil. Member of the Brazilian Art History Committee (CBHA) and the International Council of Museums (Icom Brasil).

ABSTRACT

This article analyzes the construction of the Carioca landscape as an urban experience, aesthetic identity, and visual emblem. The visions of nature and the city of Rio de Janeiro projected by the work of Marc Ferrez and its diffusion in analogical and digital media coexist today with other distinctive images of the place that subvert established imaginaries and resize the appropriations of this landscape.

Keywords: landscape; photography; Rio de Janeiro; Marc Ferrez.

RESUMEN

Este artículo analiza la construcción del paisaje carioca como experiencia urbana, identidad estética y emblema visual. Las visiones de la naturaleza y de la ciudad de Río de Janeiro proyectadas por la obra de Marc Ferrez y su difusión en los medios analógicos y digitales conviven hoy con otras imágenes distintivas del lugar que subvierten los imaginarios establecidos y redimensionan las apropiaciones de este paisaje.

Palabras clave: paisaje; fotografia; Rio de Janeiro; Marc Ferrez.

RESUMO

Este artigo analisa a construção da paisagem carioca como experiência urbana, identidade estética e emblema visual. As visões da natureza e da cidade do Rio de Janeiro projetadas pela obra de Marc Ferrez e sua difusão nos meios analógicos e digitais convivem hoje com outras imagens distintivas do lugar que subvertem imaginários estabelecidos e redimensionam as apropriações dessa paisagem.

Palavras-chave: paisagem; fotografia; Rio de Janeiro; Marc Ferrez.

When we read a book, just like when we look upon a landscape, we are reached by other readings: “each new reader is affected by what he imagines the book was in previous hands”, reminds us Alberto Manguel, in Uma história da leitura [A history of reading] (1997, p. 29). The author refers to books that come before our eyes for the first time, but the remark also applies to those that have already been before us, in other times. I think it could also be extended to reading the landscapes that we revisit with “other” eyes. The idea, by the way, is not new: “a book, like a landscape, is a state of consciousness varying with readers”, wrote Ernest Dimnet (1866-1954), in The art of thinking (1928).1

Leafing through the catalog of the exhibition A paisagem carioca [The Carioca landscape] (Martins; Caleffi, 2000), held at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, and the volume dedicated to Marc Ferrez (Turazzi, 2000), published in the Espaços da Arte Brasileira [Brazilian Art Spaces] collection, both from the turn of the 20th to the 21st century, it seemed an opportunity to reflect on the changes in the apprehension of the landscape of Rio de Janeiro, observed from where we are, that is, when the images gathered there and those created by other visions of the city began to circulate widely through digital media.

Twenty years later, the construction of the aesthetic identity of this geographic area has been deeply changed by the modes of production and circulation of the images that make up the so-called Carioca landscape, as well as by other conceptions of the very notion of landscape, polysemic word and multidisciplinary concept. Adauto Novaes, philosopher and curator of memorable debates held in the country since the 1980s, when presenting the seminar that accompanied the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, indicated a reading path for those visions of the Carioca landscape:

History breaks down into images and not into stories, writes Walter Benjamin. This idea becomes evident if we think that each transition, each passage from one landscape to another, from one lifestyle to another, from one mode of production to another, is accompanied by losses that are only compensated for by images that keep traces of the past. When an image appears as an emblem of the passage between the old and the new, instead of being just a shadow of tradition, it forgets its naive and partial side, concentrates itself the signs of rupture, what is perennial, and starts to leave us think about history. (Novaes, 2000, p. 170)

The expression that gave the exhibition its title is an emblematic synthesis of this passage between the old and the new in the representation of nature, the city and history in Rio de Janeiro. The expression Carioca landscape condenses, by itself, one of the “lieux de mémoire” of the city and one of the manifestations of a given urban visuality. As a material and symbolic construction, it breaks down into images of the place that keep traces of the past and naturalize traditions, but also point other visions of the city that instigate us to (re)think its history and to imagine other possible futures for this landscape, as a natural place site, a space of human life and a way of apprehending the world (Simmel, 2013).2

A visual history of Rio de Janeiro can be seen through the city’s relationship with the sea and its characters interweave with material and symbolic sites. The notion of “public photography” is a perspective, that is, when photography enters the conformation of the sphere of public opinion, in the public space of collective expressions and in instances of exercise and control of public power (Mauad, 2015). This article,3 benefited from the reflections presented by such studies, integrates a research on the historicity of the Carioca landscape, understood as the natural, built and represented landscape, which singles out the urban experience, the aesthetic identity, and the visual emblems of Rio de Janeiro. This approach allows us to observe the interactions and mutations in the ways of appropriating this landscape, in the past and the present.4

The point focused here is the visions of nature and the city (re)elaborated by the work of Marc Ferrez (1846-1923) and the conversion of this legacy into cultural heritage, understanding the production and dissemination of the photographer’s images as active components of the aesthetic appropriation of the landscape of Rio de Janeiro. On the other hand, these photographs and their wide circulation in analogue and digital media coexist today with other urban experiences and distinctive images of the city, which not only subvert the Edenic imaginary associated with the place, deeply rooted in Brazilian culture and in international media, but also resize the forms of appropriation of Rio’s landscape as a cultural heritage.

For this reason, “landscapes in transit”, that is, landscape conceptions and visions of the Carioca landscape that move not only in time and space, but also in our imagination.

Landscape, landscapes

The polysemy of the word landscape is usually pointed out by those who focus on the subject, whatever the intended trim for a notion traditionally traversed by ambiguity. Among the most frequent meanings, landscape is sometimes referred to as a natural site and empirical reality, sometimes as a portion of the territory reached by vision, sometimes as a space of human life and social interactions, in the countryside or in the city, sometimes as a genre of painting historically related to European art in the Renaissance, sometimes as representation through images (textual, visual, sound or mental) that are not limited to this temporality and, much less, to Western culture. Ambiguities seem inevitable and the qualifiers “natural”, “urban”, “cultural”, “human” etc. illuminate other meanings attributed to the word. For this very reason, the semantic fluctuations of the landscape notion and the reflections around the concept in different disciplines are accompanied by attempts to systematize the points of convergence and differentiation of the perspectives observed (Bulhões; Kern, 2010; Cauquelin, 2007; Corrêa; Rosendahl, 2004; Salgueiro, 2000; Schama, 1996; Serrão, 2011; Simmel, 2013).

In Brazil, the First International Art History Colloquium, held in São Paulo, in 1999, by the Brazilian Art History Committee, with the theme “Landscape and art: invention of nature and evolution of seeing” was an important milestone in the development of studies on the landscape, among other academic and cultural initiatives related to the issue. In addition to bringing together some of the main landscape theorists, such as Augustin Berque and Alain Roger, the meeting promoted the exchange of themes, approaches and research practices among dozens of national and foreign scholars (Salgueiro, 2000). Ulpiano Bezerra de Meneses, when making a critical assessment of the works presented, indicated the difficulty in establishing points of convergence for the multiplicity of perspectives on the very notion of landscape (Meneses, 2002). In another article, he deepened this reflection, systematizing the historicity, foundations, uses and correlations of the landscape with the concept of cultural heritage and its exploitation as a commodity. The author says:

The historicity of the landscape also concerns the use that societies or social segments have made of it [since] the deepest meanings of the landscape are concentrated in the uses. It would be impossible to map here, historically referenced, the main uses and functions to which landscapes were lent. Indeed, the cognitive, aesthetic, and affective mobilization capacity of the landscape means that it can be explored in the most varied directions, in which the dimension of power is always introduced. It serves as a vector to make abstract concepts concrete, such as the garden of Eden, pastoral, escape or allegorical landscapes, utopian spaces (the land of Cockaigne); the dangers, barbarism or degeneracy of the tropics (so useful for the purposes of colonial projects) or, on the contrary, its wonders and original purity. The look of the colonizer, naturalist or traveler builds multiple landscapes. The most varied conceptions of nature tamed by reason or, on the contrary, as a model to guide insufficient reason are expressed in gardens, whose history is intertwined with the whole social history ― and impose codes of specific readings. (Meneses, 2002, p. 40-41)

More recently, the collection organized by Adriana Serrão (2011) brought together some of the most relevant theories on the subject, starting with the famous essay “Philosophy of the landscape” (1913), by Georg Simmel, considered the first philosophical text dedicated to the landscape. In general terms, the approaches of this anthology are divided into three aspects: “ontology, in determining the essence and intrinsic qualities of the landscape; aesthetics, when it meets the different modes of appreciation and valuation; and ethics, by taking a position on the meaning, possibilities and limits of human action” (Serrão, 2011, p. 10). In addition to identifying the semantic evolution of the word and the historicity of the notions of landscape in the natural and human sciences, the philosophical approach inaugurated by Simmel and followed by Serrão prioritizes the intersections of a synthetic category between nature and culture, with other ethical dimensions of human existence and ways of apprehending the world:

It is a peculiar way of apprehending natural things which, precisely as a form, resides in the spirit and not in things; it is not a given state in itself, but implies a for oneself. It is this form that allows converting a multiplicity of separate elements into a homogeneous whole, which results from them, but is not reduced to their mere sum. With this position, the landscape ceases to be an unquestionable fact to present itself as a problem that must be clarified as a emotional formation and understood in the main configurations in which it was historically and culturally embodied. [...] The thesis so often repeated by culturalist theories that man shapes landscapes made us forget that landscapes also shape us. Healthy or polluted, full or poor of stimuli, they are not seen “from the window”, but are traversed and act positively or negatively on us. (Serrão, 2011, p. 17; p. 29)

For the purposes of this article, it is important to retain this holistic understanding of the concept and the premise that “landscape has a history” and that “the perceptive structures are [also] historical” (Meneses, 2002), two axes of the aforementioned systematization that underlie this reflection on the historicity and appropriations of the notion of the Carioca landscape. A landscape that is, at the same time, nature and city, since this symbiotic relationship is indissolubly linked to the aesthetic identity of Rio de Janeiro, with the caveat that such identity cannot be reduced to the picturesque and sublime vision of the place, consecrated by the trace of almost all travelers from the past. Rather, it means a more comprehensive and plural way of thinking about individual and collective experiences that take the aesthetic aspect as a salient feature of local identity, also reaching historical and cultural changes in the construction and appropriation of this landscape (D’Angelo, 2001).

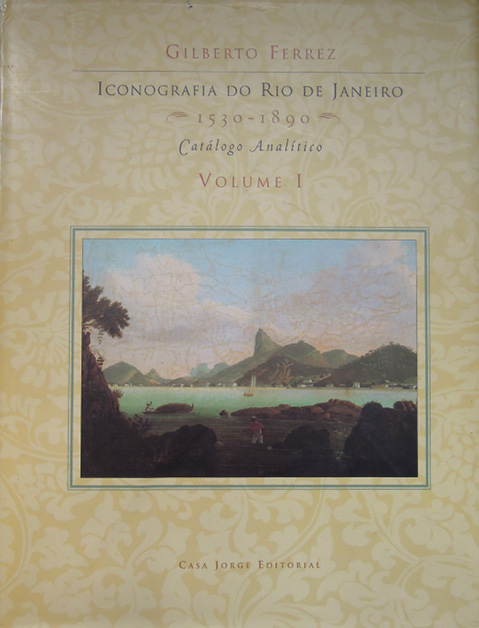

Figure 1 ‒ Catalog Iconography of Rio de Janeiro, 1530-1890 (2000), organized by Gilberto Ferrez throughout his life. Source: Ferrez (2000)

The collector and historian Gilberto Ferrez carried out, throughout his lifetime, the most complete inventory of Rio de Janeiro iconography, between the 16th and 19th centuries, located in national and foreign collections. This work had been published in the year of the death of this tireless scholar of cultural heritage, and the grandson of Marc Ferrez (Ferrez, 2000). On the same occasion, the exhibition Paisagem carioca [Carioca landscape] presented to the city’s audience the most expressive repertoire of visual, literary, and sound representations that made this landscape an identity mark of the city and one of the distinctive emblems of Brazil (Martins; Caleffi, 2000). Engaging researchers from different areas, the project brought together more than a thousand paintings, engravings, maps, photographs, sculptures, records and decorative objects, among other items from public and private collections, from which 752 works were reproduced. This image database was made available on a CD-ROM, at that time an innovative instrument for researching and disseminating historical sources. In this vast documentary collection, the web of imaginaries revealed by the Carioca landscape highlighted not only the Edenic and harmonious images of nature and the city of Rio de Janeiro, but also its metonymic function of representing Brazil:

The landscape, an imprecise frame of the colonial city in Leandro Joaquim’s perception, a mark of the identity of the city and the country, carefully studied and scrupulously fixed by the arts while the State consolidated the unity of the Empire, assumed the function of dazzling support to order with progress in the first decades of the 20th century, and was reproduced a thousand times in photographs, postcards, stamps, engravings, trays with butterfly wings, boxes, brooches, watches, and a myriad of the most varied objects that through it represented the ‘capital-city’ and, therefore, the country. (Neves, 2000, p. 30)

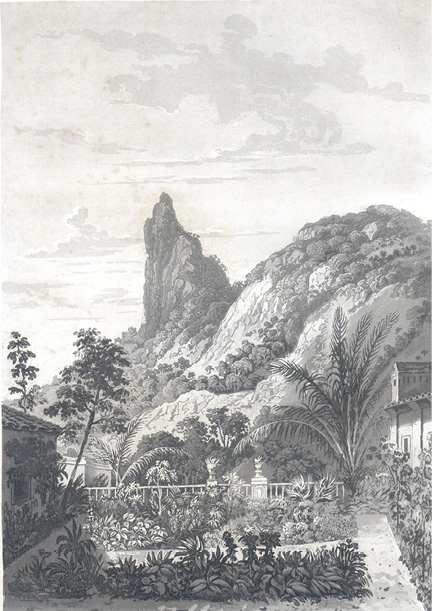

The landscape images of Rio de Janeiro in the second half of the 19th century naturally dialogue with the multiplicity of landscapes that populated the daily life and imagination of Brazilians and foreigners. Drawing, painting, and engraving, in turn, suggested conventions and themes already familiar to the European environment to the first photographers, an inevitable reference for the exploration of an aesthetic repertoire with the resources inherent to the practice of photography. The new methods of photomechanical reproduction, streamlining the visual economy, stimulate the reappropriation of landscape emblems by technical images, favoring "intermediality" in the ways of seeing and representing nature and the city. Consequently, they promoted the interactions and interchanges of different medias in the promotion and circulation of the Carioca landscape in the visual culture of the time.

Figure 2 – View of the Corcovado, lithograph. Maria Graham (drawn), Edward Finden (lithographed), 1822. Source: Geyer Collection, Imperial Museum

The photographic invention of the landscape

As a city “squeezed between the sea and the mountains”, the arrival to Rio de Janeiro has always inspired travelers with a sort of reflection marked by paroxysms. In the past, those who travelled through the Atlantic and crossed the narrow passage at the entrance of Guanabara Bay not only saw a majestic scene from there, but also had a privileged point of view for the city first critical judgment. The sinuous elevations, then depopulated and still covered by virgin forest, surrounded a modest urban area confronted to exhaustion with the exuberance of nature. The Carioca landscape delineated in most of these views and panoramas was deeply affected by the “feeling of nature” and the “geographical imagination” of traveling artists and their reinterpretation in European engraving and lithographic workshops (Simmel, 2013; Martins, 2001).

In a country with abundant and diverse vegetation, the study of the landscape as a pictorial genre took place, then, “within the four walls of a room, with the windows full of dust”, pointed Lilian Schwarcz highlighting what seemed to be a contradiction in the artistic education promoted by the Academia Imperial de Belas Artes [Imperial Academy of Fine Arts] (1822-1889). This apparent paradox in the process of invention, re-elaboration and adaptation between us of the romantic representation of the landscape is attributed by the author to the distance from the aesthetic renewal emerging in Europe, as well as to the attachment of the first generations of Brazilian artists to the academic tradition and their link “to a court that saw art as an illustrative resource of their existence and not as a dialogue with social or even natural reality” (Schwarcz, 2003).

The Carioca landscape construction through the photographic device, as one can imagine, would not occur “within four walls”, but in direct contact with the outside world. It happened since the first demonstrations of the daguerreotype by the voyageurs of the Oriental-Hydrographe expedition in the South America, including Rio de Janeiro (Turazzi, 2019). On the other hand, idealized and imaginative landscapes did not take long to be incorporated into the photographic studios of the time, as a painted background for posing photography salons or as an exotic and in natura decoration to photographs of all sorts. The famous portrait of the emperor d. Pedro II, made by Insley Pacheco, in 1883 is a distinctive example.5 Since the tremendous success of photography at the Great Exhibition (London, 1851), national and international exhibitions would expand the circulation and illustrative character of these images, enhancing their psychological effects in the apprehension and valuation of familiar and distant landscapes, most of which were only reached by a few travelers.

Aesthetic values have been invoked by photography enthusiasts since its inception, when the daguerreotype was announced as an art “without art” and “available to all”, as it was drawn by nature itself. Relying on the fidelity of the record and the accuracy of the form, it would gain notability for its descriptive and informative value when compared to other available resources. But, like drawing and other illustrative arts, photographic practice also aims aesthetic valuations, whether when its adherents evoke artistic conventions, or when they overcome the challenges encountered, creating their own solutions for the medium (Soulages, 1998, p. 137-168).

The peculiarities in the perception and elaboration of the landscape through painting and photography, or, more specifically, the historicity of the cultural experience informed by the photographic device and the displacement of meanings between the “invention of the photographic landscape” and the “photographic inventions of the landscape”, are discussed in the work Les inventions photographiques du paysage (Frangne; Limido, 2016). The authors delimit in texts and images the continuities and ruptures of landscape photography regarding the forms of totalization, ordering, unification, and composition of this genre of painting. Pierre-Henry Frangne and Patricia Limido locate in the European context, encompassed by the work, and in the years 1850-1860, analyzed by the two authors, how the photographic became an autonomous art with the invention of mountain landscape photography by the Bisson brothers, in the Alpine region. By inaugurating a new and heterogeneous aesthetic experience in relation to the world, the photographic landscape would have reached other dimensions in the perception of the natural landscape and its inscription in human subjectivity:

Such is the photographic invention of the landscape: a landscape that does not reduce the exteriority of the represented world to the interiority, spirituality and virtuosity of the artist; a landscape, on the contrary, that shows and explores the exteriority of nature and that present it as it is, without idealization or transfiguration, as a place of an infinity of images, points of view and possible experiences; images, points of view and experiences are always bodily determined and valid in themselves. (Fragne; Limido, 2016, p. 17-18, our translation)6

The “invention” of landscape photography institutes a new way of seeing nature, a gaze that repositions the role of the observer and the range of vision, promoting new forms of reception and circulation for this type of visual image. The mountainous scenery of Rio de Janeiro, which had so much attraction for artists and travelers in the past, would now be explored with other contours by the lenses of photographers, souvenir albums and travel guides addressed to the new “touristas” who arrived in the city (Perrotta, 2015).

The invention of the “luxurious” and “smiling” nature of Rio de Janeiro

The life and activities of Marc Ferrez as a prolix and versatile photographer, a trader in photographic equipment and materials, an editor of illustrated publications and a cinema entrepreneur, among other personal and professional facets, are well documented and increasingly known (Turazzi, 2005; Ceron, 2019).7 On the other hand, the images of his photographic studio helped to shape a certain image of Brazil and Brazilians in the Second Reign and early years of the Republic, for internal and external consumption, also a recurring source of investigation in historical studies on various topics.

Since the 19th century, Ferrez has been acclaimed in the international photographic world, such as the Société Française de Photographie [French Photographic Society] and the jury of several exhibitions, for the uniqueness and excellence of his photographs. He is recognized, currently, as one of the greatest names of his time. Between the second half of the 19th century and the first years of the 20th century, he was responsible for the creation and dissemination of hundreds of photographic landscapes of the country and, particularly, of Rio de Janeiro. The advertisements published by Ferrez in the Almanak Laemmert, over several years, made explicit his adherence to landscape photography, both in the “specialty of views of Brazil” (1872) and in the “specialty of views of Rio de Janeiro” (1878). These landscapes, having circulated in Brazil and abroad as single images, collected in albums, or illustrating printed material of all kinds, are today devoid of any physical and geographical barrier, thanks to the preservation and digitization of his immense legacy.8

Between the 1880s and 1890s, Ferrez carried out innovative experiments in landscape photography, such as adapting cameras to produce large-format panoramas and instantaneous marine photographs obtained from inside a boat, two examples among many others of his intimacy with the state-of-the-art photographic technologies. Participating in national and international exhibitions, he studied formats, processes, and equipment to explore in his own ways the different plastic resources offered by landscape photography, a genre already valued for the challenges, uses and functions it could associate to the representation of nature and its scientific, economic and artistic study, among other possibilities (Turazzi, 2000; 2005).

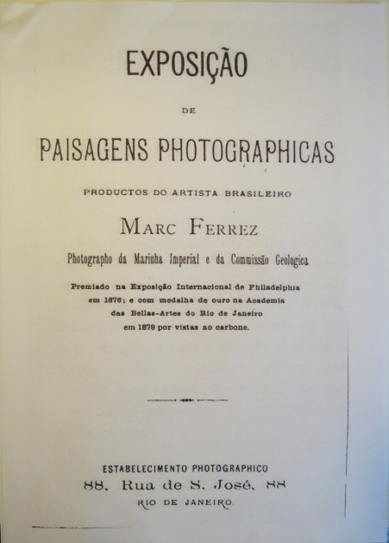

Figure 3 ‒ Marc Ferrez. Exhibition of photographic landscapes produced by the Brazilian artist. Rio de Janeiro: [Marc Ferrez House], 1881. Brochure published by the photographer for the National Industry Exhibition, held in Rio de Janeiro (1881). Source: Ferrez (2000)

In 1881, Ferrez launched the catalog Exposição de paisagens photographicas, productos do artista brasileiro Marc Ferrez, photographo da Marinha Imperial e da Commissão Geologica [Exhibition of photographic landscapes, products of the Brazilian artist Marc Ferrez, photographer of the Imperial Navy and the Geological Commission], a work that brought in the title an explicit reference to this new modality of landscape representation and the main information that accredited him as a “Brazilian artist” and a photographer commissioned by the State. Inside, he gathered explanations and images that would further illustrate the reputation of his photographic establishment. The brochure publication, in a small format, was intended for the National Industry Exhibition, held in Rio de Janeiro, in the same year, on the initiative of the Industrial Association.

The adaptation of a rotative panoramic camera to be used in the city was achieved after his visit to France, in 1878, and the acquisition of a model he found there. It was called, for this reason, the “Brandon camera”, although the equipment also relied on Ferrez’ ingenuity. The explanations given in the leaflet tried to be convincing: “all the improvements and progress that photographic art has conquered until today have been studied and used in this establishment, sparing no expense or effort to elevate it to the first place in the industrial branch to which it is dedicated and explores”; and conclusive: “the perfection of the works produced by this photographic establishment is guaranteed” (Ferrez, 1881, p. 5). In the text, he proclaims his fascination with the landscape of Rio de Janeiro, a determining feeling for the photographer’s personal choices and an inspiring theme for his work:

The large panoramic apparatus, perfected by the artist owner this establishment, was built expressly to obtain views of Rio de Janeiro that should be as important and beautiful as the splendid landscapes that are displayed in this luxuriant and smiling nature. (Ferrez, 1881, p. 6)

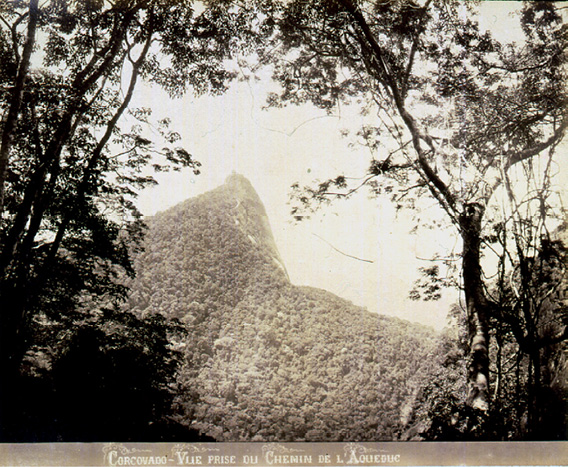

The image of Corcovado, taken from inside the forest, in the Tijuca Forest, reproduced here in two versions (Figures 4 and 5),9 represents one of the most beautiful photographic landscapes of the natural landscape of Rio de Janeiro. On the other hand, this photograph can also be read as a kind of biographical sketch of the photographer’s own personality. The scene evokes all the passion of a tireless hiker for the contemplation and appropriation of nature through the lens of his camera until the end of his days. In the small detail at the center of the image, the photographic record of the new belvedere in the city and the accurate perception of urban evolution. Between passive contemplation and studied observation, in front of one of the city’s symbolic landmarks, the Corcovado photograph exemplifies one of the most poetic moments of Ferrez’ intrinsic relationship with the construction of the Carioca landscape through the photographer’s gaze.

Figure 4 ‒ Marc Ferrez. [Corcovado], c. 1886. Photograph (albumen and silver) in digital reproduction, 21.7 x 15.6 cm. Source: Jennings Hoffenberg Collection, currently the Instituto Moreira Salles Collection

Figure 5 ‒ Marc Ferrez. Corcovado - Vue prise du Chemin de l’Aqueduc [View taken from Chemin de l’Aqueduc], c. 1886. Photograph (albumin and silver), 21.0 x 25.5 cm, placed in an album of views of the city of Rio de Janeiro. Source: João Hermes de Araújo Collection, at the time of reproduction and publication in Turazzi(2000)

In front of the imposing mountain, surrounded by vegetation, the observer is invested with the condition of supporting the photographic act. Where would Marc Ferrez be? Next to the camera that occupies the foreground of the image or behind the equipment that actually records the scene? Framing everyone, people and mechanisms, in the observation of nature and the history that unfolds and is projected over the waters of Guanabara, this photograph has the particularity of transmitting all the photographer’s complicity with the place where he was born and lived his last days.

Like any landscape, it also has the power to stir our imagination, establishing correspondences and kinships, logical or unusual, between the times, spaces and characters represented there. For this very reason, when the framing of the trees in the foreground of the composition is observed, the photograph reminds us back (and transports us) to the peaceful rest of an immense arbor, a typical construction of well-decorated gardens. While the viewer rests in the shade, the observer’s gaze is drawn far into the distance, as do the characters who join the photographer on this displacement that is work, promenade and experience. These are the gazes of the past and the present that cross the planes and the mountains lost in the horizon, amid the exuberant vegetation, under the intense sun that illuminates the tropical nature. Several temporalities overlap in this path: the moments experienced by the photographer himself and his companions (one of them, probably, his son Jules Ferrez, born in 1881), the times of capture, production and circulation of this and other photographs of Corcovado, as well as all subsequent times of a visual and sensorial experience of the landscape of Rio de Janeiro shared with other eyes.

Shaping these moments of loving contemplation and hard work in the presence of the landscape, Ferrez explored not only the effects of light, but also new possibilities of composition. He employed aesthetic resources that granted this nature special effects to make it even more touching and exuberant. In this photograph, as in others, the excursion through the forest involved the use of more than one equipment, showing Ferrez unequivocal intention to record for posterity his choices and the photographic act itself within the Carioca landscape construction process. In addition to mastering the correct exposure of the plates in contact with the humidity and high temperature of the tropics, he had absolute mastery of the results he wanted to achieve, in the forest or in the laboratory, exercising or supervising the manipulation of the technical processes for obtaining landscape photography. The development, fixation and printing of the image with refined chromatic values, captioned and mounted on a decorated passe-partout, also receives the brand of Casa Marc Ferrez and, often, its own signature in the Carioca landscape.

(Re)appropriations of the Carioca landscape

Ferrez’s photographs and his interactions with the Carioca landscape shed light on the materiality, historicity and meanings of a given “construction” of Rio de Janeiro’s landscape as a cultural heritage. In 2004, the images of Corcovado included in this article were part of the iconographic survey for the candidacy of Rio de Janeiro, presented by the National Institute of Historical and Artistic Heritage (Iphan), to the newly created category of “cultural landscape”, whose nomination as a world heritage was granted by Unesco in 2012. Other interventions and appropriations of this same landscape, as a material and symbolic space of power relations in the city and in history, began to point out the ideological dimension of these visual emblems.

W. J. T. Mitchel proposal to think about the landscape is precisely to conceive it not as an object to be seen or as a text to be read, not what it “is” or what it “means”, but what the landscape “does” as a social practice, in which subjectivities and identities are constructed as power relations:

Landscape as a cultural medium thus has a double role with respect to something like ideology; it naturalizes a cultural and social construction, representing an artificial world as if it were simply given and inevitable, and it also makes that representation operational by interpellating its beholder in some more or less determinate relation to its givenness as sight and site. (Mitchell, 2002, p. 2)10

The Carioca landscape, in addition to represent a metonymic figuration of Brazil, was transformed throughout the 20th century into a “particular geography” of the city’s places, materially and symbolically valuing some, to the detriment of all others, where emerge the ways of being and living crossed by poverty and social exclusion. The appearance of the expression “cidade maravilhosa” [wonderful city] in the first years of the Republic, and its immediate association with the Carioca landscape, would mean a form of domination and a civilizing promise, identified with the “cultural hegemony of specific social classes representations of the world” (Barbosa, 2010). Focusing on the imaginary construction of Rio de Janeiro as a “wonderful city”, Jorge Luiz Barbosa points out that:

this urban image often served as an ideological apparatus for brutal processes of displacement and destruction of forms and ways of life that are not consistent with the values and traditions mirrored in the natural landscape of the marvelous. The texture of nature’s beauty and the city’s socio-cultural sense lead us, contradictorily, to accept the compulsory utopia of the wonderful as our future and, at the same time, deny everything and everyone that deviates from the aesthetic standard of what is considered civilized. Does the landscape reveal and denounce us in what we hide? (Barbosa, 2010)

The 21st century has made photography (or what we still insist on calling like that) accessible to everyone, as it was promised since the invention announcement. The advent of digital images, revealing what we do with landscapes and what they “do” with us, provoked a radical change in the panorama examined so far. Digital media have increased, on an unprecedented scale, the production and circulation of old and recent appropriations of all spaces and characters in the city, reconfiguring choices and their contradictions. They also promoted a wide interaction between the new visual producers, fostering dialogue between interlocutors from national and foreign megacities that expanded even more the scope of the debate on the landscape(s).

Degraded areas, suburbs and, especially, the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, where the uniqueness of urban, artistic and cultural forms is evidenced by new experiences and interactions, gain increasing projection, reconfiguring what the landscape of Rio de Janeiro has become. These practices diversify strategies, subvert hierarchies and lay bare stereotypes, combining media and languages to reposition characters and places in the city, from excluded subjects to producers of their own visual narratives. This questioning today reaches researchers, photographers, artists, activists and citizens who, together, have been building another conception of the Carioca landscape. An exercise that places photography “in a critical perspective and confronts the commodity-image with the experience-image” (Mauad, 2015, p. 8).

Conclusion

The appreciation of the ways of “seeing” and “reading” the landscape of Rio de Janeiro took as a premise an integrated and transdisciplinary view of the landscape. Far, therefore, from the dichotomies that link its understanding to the oppositions between nature and culture, objectivity, and subjectivity, and so on. In this perspective, an attempt was made to intertwine the construction of the Carioca landscape with a holistic view of the landscape concept. The background chosen was the historicity of a multidimensional concept and its importance for human existence and planetary survival. With this approach, the Carioca landscape was identified as a material and symbolic creation resulting from the practices and representations that constitute the urban experience, the aesthetic identity and the visual emblems of Rio de Janeiro, throughout its history.

Constructed in the past by plastic images, today combined with other images shaped by digital means, the Carioca landscape condenses experiences about nature and the city shaped by the memory of the past, power relations and the contemporary gaze. Therefore, it can be taken as a “mold” landscape, not because it serves as an example or model for anything, but because it shapes the dynamics of social history as a collective experience in constant mutation.

Tradução de Maria Inez Turazzi

References

BARBOSA, Jorge Luiz. Paisagens da natureza, lugares da sociedade: a construção imaginária do Rio de Janeiro como “cidade maravilhosa”. Biblio 3W: Revista Bibliográfica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, Barcelona, v. 15, n. 865, 25 mar. 2010. Available at: http://www.ub.es/geocrit/b3w-865.htm. Accessed on: 2 nov. 2022.

BULHÕES, Maria Amélia; KERN, Maria Lucia Bastos (org.). Paisagem: desdobramentos e perspectivas contemporâneas. Porto Alegre: UFRGS, 2010.

CAUQUELIN, Anne. A invenção da paisagem. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2007.

CERON, Ileana Pradilla. Marc Ferrez: uma cronologia da vida e da obra. São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Salles, 2019.

CORRÊA, Roberto Lobato; ROSENDAHL, Zeny (org.). Paisagens, textos e identidade. Rio de Janeiro: Uerj, 2004.

D’ANGELO, Paolo. I limiti delle teorie correnti del paesaggio e il paesaggio come identità estetica dei luoggi. In: D’ANGELO, Paolo. Estetica della natura: bellezza naturale, paesaggio, arte ambientale. Roma: Laterza, 2001. p. 146-168.

DIMNET, Ernest. The art of thinking. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1928. Available at: https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks14/1400451h.html.Accessed on: 10 out. 2022.

FERREZ, Gilberto. Iconografia do Rio de Janeiro: 1530-1890. Rio de Janeiro: Casa Jorge Editorial, 2000.

FERREZ, Marc. Exposição de paisagens fotográficas, produtos do artista brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: [Casa Marc Ferrez], 1881.

FRANGNE, Pierre-Henry; LIMIDO, Patricia (org.). Les inventions photographiques du paysage. Rennes, France: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2016.

MANGUEL, Alberto. Uma história da leitura. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, ١٩٩٧.

MARTINS, Carlos; CALEFFI, Sandra Regina (org.). A paisagem carioca. Rio de Janeiro: Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 2000. Catálogo da exposição no Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro.

MARTINS, Luciana de Lima. O Rio de Janeiro dos viajantes: o olhar britânico (1800-1850). Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2001.

MAUAD, Ana Maria (org.). Fotograficamente Rio: a cidade e seus temas. Niterói: Universidade Federal Fluminense; Faperj, 2015. Available at: http://www.labhoi.uff.br/fotograficamente-rio. Accessed on: 12 out. 2022.

MENESES, Ulpiano Bezerra. A paisagem como fato cultural. In: YÁZIGI, Eduardo (org.). Turismo e paisagem. São Paulo: Contexto, 2002. p. 29-64.

MITCHELL, W. J. T. (ed.). Landscape and power. 2. ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

NEVES, Margarida de Souza. A cidade e a paisagem. In: MARTINS, Carlos (org.). A paisagem carioca. Rio de Janeiro: Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 2000. p. 20-31.

NOVAES, Adauto. Seminário Paisagem Passagem [Apresentação]. In: MARTINS, Carlos (org.). A paisagem carioca. Rio de Janeiro: Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 2000.

PERROTTA, Isabella. Promenades do Rio: a turistificação pelos guias de viagem de 1873 a 1939. Rio de Janeiro: Hybris Design, 2015.

SALGUEIRO, Heliana Angotti (coord.). Paisagem e arte: a invenção da natureza, a evolução do olhar. São Paulo: CBHA; CNPq; Fapesp, 2000.

SCHAMA, Simon. Paisagem e memória. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1996.

SCHWARCZ, Lilian Moritz. Estado sem nação: a criação de uma memória oficial no Brasil do Segundo Reinado. Artepensamento IMS, 2003. Available at: https://artepensamento.ims.com.br/item/estado-sem-nacao-a-criacao-de-uma-memoria-oficial-no-brasil-do-segundo-reinado. Accessed on: 31 out. 2022.

SERRÃO, Adriana Veríssimo (org.). Filosofia da paisagem: uma antologia. Lisboa: Centro de Filosofia da Universidade de Lisboa, 2011.

SIMMEL, George. Filosofía del paisaje. Madrid: Casimiro, 2013 (Die Philosophie der Landschaft, 1913).

SOULAGES, François. Esthétique de la photographie: la perte et le reste. Paris: Nathan, 1998.

TURAZZI, Maria Inez. O Oriental-Hydrographe e a fotografia: a primeira expedição ao redor do mundo com “uma arte ao alcance de todos”. Montevidéu: Centro de Fotografía de Montevideo, 2019. Available at: https://issuu.com/cmdf/docsAccessed on: 12 out. 2022.

TURAZZI, Maria Inez. A vontade panorâmica: cronologia. In: TURAZZI, Maria Inez. O Brasil de Marc Ferrez. São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Salles, 2005. p. 14-55; 305-314.

TURAZZI, Maria Inez. Marc Ferrez. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify, 2000. Coleção Espaços da Arte Brasileira.

Received 4/11/2022

Approved 3/2/2023

Notes

1 Ernest Dimnet, a French priest and thinker, published several works that were very popular in the 1920s and 1930s, including The art of thinking (New York, 1928), originally published in English and later published in French (Paris, 1930).

2 George Simmel (1858-1918) published Die Philosophie der Landschaft in 1913.

3 The article develops the communication originally presented at the roundtable “The captured city: photography and history in Rio de Janeiro”, coordinated by Professor Ana Maria Mauad, at the seminar on Rio 450 years of history, at the Casa de Rui Barbosa Foundation, held from September 14th to 19th, 2015.

4 The project “Landscapes of Rio: ways of seeing and reading the city (2016-2019)” was supported by CNPq, integrating the Memory, Art, Media research line of the Oral History and Image Laboratory of the Fluminense Federal University.

5 The portrait of D. Pedro II, printed in platinotype and presented in exhibitions at the time, is reproduced on the Brasiliana Fotográfica portal, available at: https://brasilianafotografica.bn.gov.br/?p=4400.

6 “Telle est l’invention photographique du paysage: un paysage qui ne ramène pas l’extériorité du monde représenté à l’intériorité, à la spiritualité et à la virtuosité de l’artiste; un paysage au contraire qui montre et explore l’extériorité de la nature et qui nous la montre comme elle est, sans idéalisation ni transfiguration, comme le lieu d’une infinité d’images, de points de vues et d’expériences possibles; images, points de vue et expériences toujours corporellement déterminés et qui valent pour eux-mêmes” (Frangne; Limido, 2016, p. 17-18).

7 The Ferraz Family archive is under the custody of the National Archive (Brazil).

8 Marc Ferrez’s collection of glass negatives and other photographic materials, as well as photographs and albums from Gilberto Ferrez Collection, are at Instituto Moreira Salles, responsible for cataloging and digitizing this heritage, as national and international institutions are doing with other images by the photographer.

9 The digital print of this image was made available for sale by Instituto Moreira Salles.

10 Unfortunately, this book is not yet translated and published in Brazil.

Esta obra está licenciada com uma licença Creative Commons Atribuição 4.0 Internacional.