Acervo, Rio de Janeiro, v. 36, n. 3, Sept./Dec. 2023

The archive as object: written culture, power, and memory | Thematic dossier

Heritage, archive, and memory:

an analysis of the Final Peace Agreement between the Colombian Government and the Farc-EP

Patrimonio, archivo y memoria: un análisis del Acuerdo Final de Paz entre el Gobierno de Colombia y las Farc-EP / Patrimônio, arquivo e memória: uma análise do Acordo Final de Paz entre o Governo da Colômbia e as Farc-EP

Jaime Alberto Bornacelly Castro

Professor at the University of Antioquia, Colombia. Ph.D. student in Social Memory and Cultural Heritage at the Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPel), Brazil, pursuing a dual degree with a Ph.D. in Social Sciences from the University of Antioquia, Colombia.

Maria Letícia Mazzucchi Ferreira

Ph.D. in History from the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS). Emeritus professor at the Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPel), Brazil.

Abstract

The article analyzes the relationships among heritage, archive, and memory based on the process of heritage-making in the Peace Agreement conducted between the Government of Colombia and the Farc-EP. The main point of discussion is the relationship among the cultural property of archival character of documentary interest, the documentary-monumental logic, and memory as a plural and open representation of the past that activates performative acts and memory militancy.

Keywords: cultural heritage; collective memory; archives; Colombian armed conflict.

Resumen

El artículo analiza las relaciones entre patrimonio, archivo y memoria a partir del proceso de patrimonialización del Acuerdo de Paz realizado entre el Gobierno de Colombia y Las Farc-Ep. El principal punto de discusión es la relación entre el bien de interés cultural de carácter documental archivístico, la lógica documental-monumental y la memoria como una representación plural y abierta del pasado que activa actos performativos y militancias memoriales.

Palabras clave: patrimonio cultural; memoria colectiva; archivos; conflicto armado en Colombia.

Resumo

O artigo analisa as relações entre patrimônio, arquivo e memória a partir do processo de patrimonialização do Acordo de Paz realizado entre o Governo da Colômbia e as Farc-Ep. O principal ponto de discussão é a relação entre o bem de interesse cultural de caráter documental arquivístico, a lógica documental-monumental e a memória como uma representação plural e aberta do passado que ativa atos performativos e militâncias memoriais.

Palavras-chave: patrimônio cultural; memória coletiva; arquivos; conflito armado na Colômbia.

Introduction

The Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia — People’s Army (Farc-EP) have created, between 2013 and 2016, a series of documents deriving from peace talks between these two actors who were in a military and political conflict for over sixty years. This file, which arose from a political pact, was declared a cultural interest good of cultural and archival character at the national level — henceforth BIC-CD — and included in 2018 at Unesco’s Memory of the World Register, once these documents represent a contribution to humanity since they will serve as model to negotiations on countries that experience similar transition situations regarding armed conflict (Archivo General de la Nación, 2018).

This heritage archive expresses a series of symbolic and ideological representation of groups and subjects associated with the internal armed conflict in Colombia. In its turn, the archive converted into heritage hides and renders invisible dissenting postures in the peace process, which was carried out with one of the most ancient guerrillas in Colombia and the world. The participation of victims, perpetrators, political leadership, women, civil society, and the international community in the negotiations of the Final Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace — henceforth FA — shows diverging and converging meanings of the past, present, and future of Colombia, in aspects such as economy, use, land ownership, construction of truth, compensation for victims, transitional justice, gender, and political participation.

Within this context, the patrimonial value of the Final Agreement (FA) archive stems not only from its national declaration by the National General Archive and by an international institution such as Unesco, but also from its relational characteristic, once it combines a set of social actors and local and global entities. Besides that, it is a difficult heritage, once it leads, in the current political context, to speeches, celebrations, emotions, and memories that are disputed. This conflictive and disputed characteristic happens, according to Le Goff, due to the fact that the document-monument is a product of and produces certain power relations, as well as it is used to convey a memory for the future based on the present time (Le Goff, 1996, p. 12).

As a matter of fact, the FA led to a series of interpretations, controversies, social mobilizations, and, paradoxically, some of the items covered by these patrimonial documents, such as land reform, illicit crops, the end of drug trafficking and paramilitarism, have resulted in the systematic assassination of social leaders, former combatants who were signatory of the peace, and members of security forces during seven years of its implementation. That is, the FA works as an official historical narrative, as many peace pacts have since the 19th century until nowadays; at the same time, it operates as a heritage that triggers fears, rights, memories, and emotions for those who oppose to a outcome negotiated with armed insurgencies.

The FA, as heritage and memory, engenders a meaning economy that goes beyond the documentary and archivist dimension in which it was made a heritage, being transformed into a memory technology (Vera, 2015). It has given rise to other documental productions and archives, such as the Peace Library, exhibitions, monuments, counter-monuments, places of memory, and celebrations. Besides that, it operates directly on contexts of continued political violence, in areas with geographical gaps, and it works as a transition device for the construction of complete peace, one of the main government policies by Gustavo Petro Urrego (2022-2026).

Within this understanding framework, this article’s aim is to analyze the relationship among heritage, archive, and memory based on the process of transforming the Peace Agreement signed between the Colombian Government and the Farc-EP in 2016 into a heritage. The main discussion point are the flows and interactions that happen between a cultural good of Document and Archive Character included in the Unesco’s Memory of the World Register, the document-monument rationale with which Jacques Le Goff invites us to reflect on memory as a plural, open, and subjective representation of the past that triggers performative acts, memorial engagement, and negative and positive emotions within social context such as the Colombian one, which resist to leave war, despite being also constructing land peace.

The methodology used in this study is hermeneutic and phenomenological once it employed interpretative instruments over official narratives, academic bibliography, and archive files, in combination to field work, including observation, visits, interviews, and photographic registries of places such as the Peace House and the Cultural House La Roja, in Bogotá, created by former Farc-EP combatants who have signed the Final Agreement. Besides that, the study included the participation in the celebration of the fifth anniversary of the Final Agreement signature, called “Peace is productive”, in the city of Medellín.

The article is divided into four sections: the first provided a political context about the Final Agreement (FA) signature; the second section covers the concepts of heritage, archive, and memory. The third part describes the archivist and patrimonial dimension of the Final Peace Agreement, highlighting its formal and legal elements; and lastly, the FA is analyzed based on the understanding keys of heritage, of the document-monument notion by Jacques Le Goff, and of memory as an object and field of knowledge that is always open, subjective and plural.

Political context of the Final Peace Agreement

The Colombian State and the Farc-EP guerilla, founded in 1964, have attempted to reach peace agreements in four occasions. The first one happened during the Belisario Betancur government (1982-1986); the second during the Cesar Gaviria Trujillo term (1990-1994); the third during Andrés Pastrana Arango’s term (1998-2002) and, lastly, during the Juan Manuel Santos Calderón government (2010-2018), when was signed the Final Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace. The FA was signed on September 26th, 2016, by the president of the Republic of Colombia and Nobel Prize laureate Juan Manuel Santos Calderón and the top leader of the Farc-EP, Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri, in a public event on the symbolic city of Cartagena de Indias. After being submitted to a referendum, it was signed again by the part on November 24th at the Colón Theatre, in Bogotá, another important place for the national culture and monument. At the Flag Square of the Convention Center of Cartagena, over 2,500 national, regional, and international personalities were present, including the United Nation’s Secretary-General, Ban Ki-Moon, and the event was widely covered by the main worldwide newspapers and portals. This agreement is significant once it concerns the most ancient armed conflict in the world, which led to nine million victims and 450,664 assassinated people between 1985 and 2018 (Comisión de la Verdad (Colombia), 2022).

In the first version of the Agreement between the Government and the Farc-EP, which was submitted to a referendum on October 2nd, 2016, the question asked to Colombian people was: “Do you support the Final Agreement to end the conflict and build a stable and lasting peace?”. The result was as it follows: 6,377,482 (49.78%) voted YES, and 6,431,376 (50.21%) voted NO. With a difference of only 53,890 votes, NO won, thus characterizing a polarized society, in which emotions such as reconciliation and hate occupied the extreme ends of the political spectrum. This result led to the creation of a new final agreement, making changes and specifications to the original agreement, although it did not imply on structural adjustments, in almost all negotiated items. This new FA was signed on November 24th, 2016, at the Colón Theatre, by both delegations, companions, and international witnesses.

The Referendum for Peace expressed feelings and emotions related to the past-present in opposite directions. The constituents who voted YES valued in a positive light the effects of the unilateral ceasefire by the Farc-EP, which represented an immediate future with no combatant and civilian deaths, as well as a reduction of the heroic speech that fed the idea of an endless war. On the other hand, the constituents who voted NO focused on the period of great military successes of public forces against the Farc-EP, specially by the democratic safety policy by the Uribe Vélez government (2002-2010), on the failed previous peace processes attempted with this guerilla, on the responsibility by the human rights and humanitarian international right violations by the insurgencies, and were uncomfortable in imagining a political future of coexistence with former guerilla members in daily scenarios and in the public power. In this sense, the Referendum for Peace was a legal-political device to use the past, in which the defenders of NO wished to go back to a past of endless war against the insurgencies. Likewise, it was also a use of the present-future by part of the constituents who voted YES, once it represented a period of peace that could be kept in the future. Banguero (2019) analyzes this relationship between past-future and politics, affirming that, during the Juan Manuel Santos government, the pendulum was on the end of negotiated peace, of peace with no victors and defeated, the words associated with this purpose were conflict, negotiation, conciliation, post-conflict, transitional justice, reconciliation, and coexistence (Banguero, 2019, p. 11).

The Final Agreement was spread through social networks in a quick and fragmented manner. There was more media exposure than pedagogical processes created to take ownership of its content. Put the manner in which this document was shared in virtual spaces into context, in Colombia, 64% of the people read digital materials in social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc., while only 28.2% of them read articles or academic documents in digital means (Departamento Nacional de Estadistica, 2017). That is, according to reading and cultural consumption data, the high volume of information and the lack of pedagogy of the Final Agreement have set a scenario of disinformation and exaltation of passions and political emotions.

In fact, this document was the object of many assessments by groups that oppose to a negotiated solution with the guerillas and consider this pact as an expression of “gender ideology”, “communism”, and “castrochavism”, as well as an object that represents the moral evil and internal enemy. Therefore, the Final Agreement was seen as “a system of despicable impunity”, “the kingdom of the Farc”, “the peace agreement means starvation for Colombia”, “the agreement wrecks the country for good”, “an impoverished desert under the domain of criminals”, “not an act of peace, but a declaration of war”, etc. These expressions were the keywords and hashtags circulating social networks and transmitted in word of mouth under the “authorized”, “canonic”, and “literal” interpretation of political leaders.

On the other hand, many materialities and memory and heritage devices arose in the defense of the Final Agreement (FA), representing opportunities to build peace and to reconstruct the social fabric (Guerra, 2019; Mouly; Giménez, 2017). Among them are the “Fragments” counter-monument, the “Kusikawasay” monument, the “Peace! Believe it to See it!” exhibition, the Open Library of the Peace Process, available on the web, just as the celebrations and performances carried out by peace signatories on the FA’s fifth anniversary in 2021, at the public square in Medellín and Bogotá. During this celebration, the participants used many exposure repertoires, covering themes such as the assassination of former combatants who had signed the agreement (Figure 1), the violation of agreement items by the government, artistical performances, and the installation of a fair called “Peace is productive”, in which objects-products were offered, such as coffee, beers, honey, clothes, backpacks, etc., all of which were produced by women and men who had signed the peace agreement (Figure 2).

Figure 1 ‒ The photograph shows a report made by former combatants regarding the assassination of signatories of the Peace Agreement during the fifth anniversary of the signature. Source: Jaime Bornacelly, 2021

Figure 2 ‒ “Peace is productive”. Both the coffee (left) and beer (right) are ventures created by women and men who have signed the Peace Agreement, and they were sold to the public during the celebration of the fifth anniversary of the signature and delivery of arms in cities such as Medellín and Bogotá. Source: Jaime Bornacelly, 2021

Heritage and archive as an active process

Heritage is a socio-cultural and political construction (Hernández; Tresseras, 2007; Prats, 2005), defined by Prats (2005) as a system of symbolic representations that construct individual and collective identities, as well as a form of valuing and strengthening the cultural identity of groups and societies. From this perspective, heritage represents postures and ideologies produced in specific times and spaces. Thus, objects, places, and subjects, as well as the expressions connected to them, are mutable. According to this logic, Harrison affirms that cultural heritage is not merely a passive process of preserving things that remain from the past, but an active process of constructing a set of landscapes, materialities, objects, places, and practices that we choose to keep as a mirror to the present, connected to a specific set of values we wish to take with us for the future (Harrison, 2013, p. 4).

This notion of cultural heritage highlights many aspects analyzed by Lähdesmäki, Zhu and Thomas. The first element concerns an active and relational process, since it intertwines spatialities, actors, and materialities, combining tangible and intangible dimensions from culture and uniting many entities, beings, institutions, and actors from the local and global scale; the second aspect is its present characteristic, as it is used by actors and agents in the present, creating memories, ideas, emotions, and identity processes that affect the future; the third one demands a process of valuing and cultural choice, it thus comprises inventions that are fabricated and managed to obtain symbolic effects, construct meanings, and produce senses (Lähdesmäki; Thomas; Zhu, 2019).

Heritage valorization puts aside other cultural referents, objects, artifacts, and products that, at the historical moment of their activation, may seem “inconveniences”. Within this context, we speak of emerging heritages, uncomfortable heritages, marginal heritages. Some characteristics of these other-heritages (Paiman; Araújo, 2018) may not be socially accepted in a specific social context, being marginalized and made invisible in certain periods and context, even though they can be socially and institutionally activated and recognized. When social or political changes happen, it means that a certain cultural heritage can belong to the heritage shadow for years and then emerge in light of the activation and official recognition, maybe to dive into the shadows once again if the social or political context changes. Uncomfortable heritages are thus fluid, porous, and borderline, considering that, as a process, they always move in the delicate border between shadow and light, discomfort and comfort, oblivion and memory (I Martí, 2010, p. 10).

Based on a critical perspective on heritage, Rufer analyzes heritage as a state representation of the past, full of solemnity, unquestionable truths, seemingly unwavering narratives, once what is heritage, in its material dimension, is transformed into evidence and proof of what really happened, putting other narratives aside, which emerge as shadows or ghosts. Memory, based on heritage, is a public exposure, a past performed for future generations, and a device to activate the past by the State or hegemonic narratives (Rufer, 2022). In this sense, talking about heritage based on critical perspectives raises the following questions: who values the past? How is this value transmitted? In what ways is a past empowered to be spoken of and to become public? Who keeps and manages it?

For Rufer and Prats, based on different epistemological coordinates, heritage and patrimony processes are pierced firstly by the sacralization of the cultural exterior and of what is displayable; secondly as a device that dialogues to, creates tension and hierarchizes different systems of representation, objects, and memory institutions, such as museums, libraries, archives, or monuments, which, one way of another, are interpreters, according to Rufer, of regimes of truth, authority, and solemnity, canon perspectives over the history that the memory, in a broader sense, questions, challenges, and strains. If the heritage discourse is more connected to the used of the past by the State, memory problematizes official narratives.

In this sense, the archivist heritage we analyze in this article arises from a transition process in which the victims are in the spotlight of the restorative justice implemented in Colombia. Therefore, the Peace Agreement that was turned into heritage and preserved in the National General Archive is closely connected to the defense of human rights, to complying to the right to truth, to justice, and to the duty of memory by the state. Thus, this archive is a key piece in the development of transitional justice processes, once it contains ideas, proposals, and amotions of the groups of victims and social actors involved in war and in the struggles for peace. Due to this characteristic, the UN recommends that the archive and documents related to the violation of human rights in post-conflict contexts should be guarded, organized, described, and accessed by the national archive entities (Giraldo Lopera, 2017, p. 129).

Archives in contexts of war or authoritarian regimes can be understood as symbolic places and objects of memory, which are fundamental for the process of seeking justice, of fighting disbelief and the will to forget (Giraldo Lopera, 2017, p. 126). Giraldo, within the understanding coordinated of the Terry Cook file, considers archives currently as a place where collective memory is constantly built. That is why documents are not an empty template in which facts and events are registered, but a construction in constant change and a set of meanings and cultural senses in constant update (Giraldo Lopera, 2017, p. 126-127). Archived memory, according to Taylor (2010), exists in the form of documents, literary texts, letters, videos, movies, etc., and, unlike the incorporated memory expressed in repertoires and performances, it implies a permanence through time and the localization in a space. However, archives are not passive nor neutral; they are in constant construction and are products of power and monumentality relations. Nothing that the families, scientists, politicians, and institutions archive is impartial or neutral; everything bears the mark of the people and actions that have saved them from oblivion (Catela, 2002, p. 402-403).

To Le Goff, every document is a monument because it is produced and selected from certain power relations in a specific society. Therefore, the document-monument is a product and a producer of social relations, the result of a conscious or unconscious editing of a time, and it keeps on living in other times in spite of forgetfulness, manipulations, and silences. It is thus an effort of historical societies to impose to the future a certain image of themselves and it expresses a "cultural unconsciousness" (Le Goff, 1996, p. 14-15).

This critical notion assumes that there is no truth-document; on the contrary, every document is true and false at the same time, since it is an appearance, an editing that the critic must unveil. This object is thus a testimony or message of a polyvalent power, since it involved complex connections of meanings, actions, actors, and social contexts in specific production conditions. In sum, the document-monument has distinct characteristics, such as being remnants of material culture, expression, and a true and false instrument of power, a testimony or messenger, a system of relations that creates collections, as well as emotional objects. What is written, the text, is more often a monument than a document (Zumthor cited by Le Goff, 1996, p. 11); that is why, for Hartog, heritage, the alter ego of memory, is connected to the land, to the identities that are reinvented, and it invites us to celebration (Hartog, 2007, p. 180-181).

In turn, in Halbwachs, memory refers to recollections constructed based on the present, within specific social frameworks. We make memories of that which, within society, is meaningful and emotionally worthy of recalling, once the person evokes their memories based on the social frameworks of social memory. In other words, the many groups who compose society are able, at every moment, to rebuild their past (Halbwachs, 2004, p. 335-336). For Jelín, when analyzing contexts of border-experiences, memory is the way in which subjects build a meaning of the past, in its connection, in the act of remembering/forgetting, with the present and desired future (Jelín, 2018, p. 272). This subjective characteristic that is constantly under construction makes memories the object of disputed, conflicts and struggles, drawing attention to the active role that produces meaning played by the people taking part in these struggles, integrating power relationships (Jelín, 2002, p. 3).

In the case of the Peace Agreement (FA), the concept of conflicts about memory, by Joel Candau (2002, 2004), is expressed by the fact that this documental heritage represents and contains one of the versions of the armed conflict past, setting other narratives aside, especially those of the groups and actors that opposed to the peace referendum. These disputed and diverging memories about past events, based on the present, are characterized by the memorial activism, by the actors’ repertoires, and by the group identities affirmations at the public arena, a privileged space for performative acts and for the legitimation of memory. It is precisely at this level of memory representation modalities that the relationships between institutional and disruptive logics are intertwined, as it also happens with relationships among heritage, archived memories, and incorporated memories.

The Final Agreement as an archival heritage

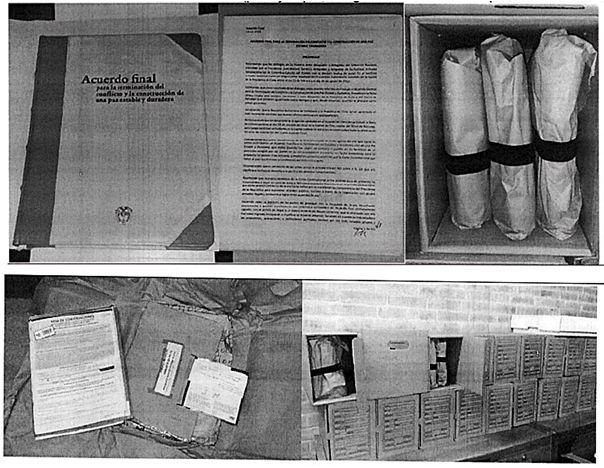

Regarding its archival dimension, in the Resolution n. 603, from August 22nd, 2018, issued by the National General Archive, the heritage archive is composed by a set of documents and objects produced during the process of negotiation, such as: the final agreement to end the armed conflict and build a stable and lasting peace (November 12th, 2016) – 155 pages (one folder); final agreement to end the armed conflict and build a stable and lasting peace (November 24th, 2016) – 145 pages (one folder); minutes of conversation tables – 118 pages (one folder); proposals by the citizens and organizations for the Final Peace Agreement (2016) composed by 42 sequentially-numbered packages and two unnumbered packages, containing forms, information handling and systematization protocols, and blank formats. Altogether, there are six linear meters (6 m), with the intention to safeguard and ensure the proper use of the nation’s documental archive (Archivo General de la Nación, 2018).

Figure 3 ‒ Archive of the Final Peace Agreement between the Colombian Government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army. It is a heritage archive that contains both FA versions, as well as a series of documents and photographs preserved by the National General Archive of Colombia. Source: National General Archive. Jorge Palacios Preciado

Figure 4 ‒ Open Library of the Peace Process. It contains both the heritage archive and other kinds of texts that aim to contextualize, explain and communicate the main aspects of the Final Agreement (FA). Source: https://bapp.com.co/

The text resulting from the negotiation, submitted to popular consultation and signed by both parties, is a 310-page document, written in Spanish, structure with a foreword, introduction, six agreed items, protocols, annexes, an amnesty act, and signatures, establishing a difference from classic international treaties from the 18th century (Nathan, 2018). It was signed on November 12th, 2016, in Havana, as a result of the Conversation Table that was officially settled on October 18th, 2012, at the city of Oslo and continued in Havana until August 24th, 2016. It was signed by Humberto de la Calle, chief of the Negotiating Team; Sergio Jaramillo Caro, High Commissioner for the Peace; and Roy Barreras, plenipotentiary negotiator; at the Farc-EP side, by Iván Márquez, chief of the Negotiating Team; Pablo Catatumbo and Minister Alape, as representative members. As the guarantor countries, Ivan Mora, representative of the Cuban government, and Dag Halvor Nylander, representative of the Kingdom of Norway.

Seven original copies with annexes were signed and distributed to the guarantor countries, Norway and Cuba, and to the accompanying countries, Venezuela and Chile; to the Federal Swiss Council in Bern, as a depositary of the Geneva Conventions; and one copy for each of the signing actors. In the case of Colombia, the FA archive was filed in the National General Archive – henceforth NGA – and later on declared as a good of national cultural interest – GNI – and then assigned, by the general-director, Armando Martínez Garnica, for the Latin American and Caribbean Memory of the World Register in 2017, bring accepted by it in a meeting conducted on October 22nd and 23rd, 2018, at Panama (Mowlac/Unesco, 2018).

The reasons given for this nomination are authenticity, national significance, comparative criteria, material, theme, and social relevance. Indeed, the archives are authentic and original, once they are products of the negotiations conducted between the Government and the Farc-EP; there is also the participation of victims, members of civil society, and of the armed forces. These documents contain signatures and initials that testify their authorship and authenticity and were products of direct transference between the office of the High Commissioner for Peace, subordinated to the Presidency of the Republic, and the National General Archive (Archivo General de la Nación, 2017, p. 5).

As for the national importance, the material and the theme of the proposed good, the statement of reasons highlights the relevance of this primary resource for the country, since it represents a process that seeks to end fifty years of internal armed conflict. It is the register of one of the most important political and social events of the contemporary Colombian history and, thus, a contribution to humanity, once it will serve as negotiation model for countries who undergo similar transition situations regarding armed conflicts. Besides, it is conferred a unique and irreplaceable value to take a significant step toward reconstructing the social fabric, and its primary values are still in force, while secondary values can already be considered part of the document, cultural, and national identity heritage (Archivo General de la Nación, 2017, p. 5).

As a heritage that represents a historical moment, the Final Agreement document was signed by a “bulletpen”, a pen designed in 2016 by the McCann agency and that received many awards at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity. This peace sign was fabricated with .50 caliber bullet casings without gunpowder, used in the context of the armed conflict in Colombia. Five hundred copies were produced and delivered by the government to activists, artists, writers, and to the top leader of the Farc-EP. The bulletpen has an engraved phrase on one of its sides that says: “Bullets marked our past. Education, our future”.

In legal terms, the Final Agreement was promoted by the Republic Congress through Law n. 2, from May 11th, 2017, as a constitutional transitory article and a public policy of the State, due to its strategical value (Congreso de Colombia, 2017). Later on, it was declared constitutional by the Constitutional Court on October 11th, 2017, by the statement C-630/17, in which its value as a public State policy was ratified (Corte Constitucional de Colombia, 2017). In the international scenario, this public policy is taken by the parts as a Special Agreement in the terms of the article 3, common to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, and, according to the ICRC opinion, it is inserted in the international legal framework once it constituted a development and application of the International Humanitarian Right and International Human Rights. In this sense, the Final Agreement is a human rights archive.

The heritage good, besides the document that was signed by the parts and transformed into State policy, also contains other documents and objects that are integral part of the archive and are included in the digital resource of the Open Library of the Peace Process (https://bapp.com.co/), in which citizens can access both the historical archive and new publications that contribute to understanding and contextualizing the Final Agreement (FA). This pedagogical and ethno-communicative strategy contains photographs, videos, texts, infographics, audio files, timelines, as well as the FA translated to 44 native languages of Colombia and to English. Among these archives, the participation of social organizations is highlighted, especially of the movement of women for peace, which was able to strain, polemize, and problematize the gender perspective in the public scenario and in the construction of peace.

The FA content is divided into six points, namely: 1. Comprehensive Rural Reform – towards a new Colombian countryside; 2. Political Participation – a democratic opportunity to build peace; 3. End of the Conflict; 4. Solution to the Illicit Drugs Problem; 5. Victims, in which the Comprehensive System for Truth, Justice, Reparations and Non-Recurrence is created; and 6. Implementation, Verification and Public Endorsement (Presidency of the Republic; Farc-EP, 2016). Point 3 is composed by two parts: a) agreement between the National Government and the Farc-EP on the bilateral and definitive ceasefire and cessation of hostilities and the laying down of arms; and b) agreement on guarantees of security and the fight against criminal organizations.

Among many other points of the FA, we highlight the parties’ recognition of human suffering as the first point that needs to be mended: “The conclusion of hostilities will first and foremost represent the end of the enormous suffering that the conflict has caused”. A second discursive element if the future hope and expectation the FA intends to project: “the end of the conflict will herald a new chapter in our nation’s history” (Presidency of the Republic; Farc-EP, 2016, p. 6). And a third aspect is the understanding that the Colombian armed conflict was caused and reproduced by social, economic, political, and subjective factors that must be overcome to build a stable and lasting peace. In this sense, the land, gender, and differential approach used in the design and negotiations of the FA between both parties is a key to understand the narrative, which, in terms of politics and ideology, represents a series of social, economic, and cultural reforms that must be implemented by the Colombian State for many decades to come.

In fact, the notion of land peace recognizes that the armed conflict has affected some regions more intensely than other, and, thus, these cities and states must gain more focus by institutional efforts in order to disengage the caused and factors that reproduce war, such as land ownership, poverty, substitution of illicit crops, inequalities in the access to rural properties and the guarantee of human rights for the inhabitants of rural and peripheral areas, such as farmers, Indigenous groups, and Afro descendant communities. “All of Colombia’s regions and territories will contribute to the implementation of the Agreement, with the participation of territorial-based authorities and the various sectors of society” (Presidency of the Republic; Farc-EP, 2016, p. 6). In this sense, land peace is cross-sectional regarding a comprehensive land reform, just as the political participation of other forces that were excluded from the Colombian political system, from which we highlight the role of women in political participation, of Indigenous communities, Afro descendant people, left-wing organizations, victims, etc. These last ones, the victims, were included in the FA as political subjects and given 16 seats in the Colombian Congress.

Among heritage, memory and archive

The Final Peace Agreement, in a relational perspective, is connected to a system of objects, repertoires, heritages, and memories. As a cultural object or artifact, it is a documental archive that was intentionally constructed, selected, preserved, and spread by many state institutions and social actors. One of its characteristics is its virtual potential, that is, what it may come to be, to transform into, or mediate, using Lévy’s terminology: in opposition to what is possible, static and already built, the virtual is like the problematic complex, the knot of tendencies or forces that comes with a situation, an event (Lévy, 1996, p. 16). In other words, the meaning of the object is not only in its material, objective, or literal dimension; it lies on the potentiality of what it may come to be, on the subjectivities it mediates, on what it suggests, hides, and on the transformations it suffers and unleashes by interacting with other practices and materialities, as in a constant flow of life.

On the other hand, the Final Peace Agreement is a long-term reification of the processes of constitution of Nation-States, that is, it is a national heritage that is materialized into historical objects that express contradiction and ambivalence in face of a land reality where violence persists and where more peace and coexistence negotiations are sought. This document texture, written by hands that are placed in diverse ideological spectrums and a result of the pact between the State and the Farc-EP, is part of an official historical narrative that is typical of institutional patrimony processes. However, many actors, both national and global ones, add new meanings and significances, just as roughness and cracks, as if they were tears or reinstatements on the document.

Indeed, the Final Peace Agreement is a palimpsest that remains, but is also rewritten throughout time and social space as groups and social actors publicly reject or reclaim the Havana agreements, in that which Taylor calls a performance, understood as incorporated memories or incarnated behaviors, in which memories, identities, and political claims and transmitted through a system of learning, storing, and transmitting incorporated knowledge (Taylor, 2010). This incorporated memory, despite not intending to substitute archived memory, challenges the prevalence of what is written in the Western world. In this sense, the celebrations that former Farc-EP combatants have been making in many Colombian cities on November 26th are examples of the relationships and bonds between archived memory and performance as an incorporated memory.

Therefore, the Final Agreement is turned into heritage by breaking with meanings in the State and Farc-EP scope, directed to other meanings and used by the citizens and political groups that confront each other in the public sphere, especially due to the participation of subject-victims in the construction of this peace agreement, which is registered in the documents that are part of the records declared as a cultural interest good, just as in the opposition’s critiques, which are also recorded in this archive. In fact, turning materialities that symbolize peace, such as the Final Agreement, into heritage in a context of continuous violence and political polarization, as in the Colombian case, activates conflicts regarding the memory (Candau, 2004), seen as versions of the past, based on the present, that confront each other in the public space, about these disputes on memory that, as affirmed by Candau, in modern societies, each individual’s feeling of belonging to a plurality of groups makes it impossible to build a unified memory and leads to the fragmentation of memories that favors confrontations (Candau, 2002, p. 13).

This document-monument, in Le Goff’s terminology, materializes a past and present history, being a symptom and symbol of a time and expressing a "collective unconscious". It registers the passing of time including new actors, languages, social, cultural, and economic investments that were not recorded in previous peace negotiations, such as the victims, the gender perspective, and the land focus, just as an Integral System for Truth, Justice, Reparation, and Non-Repetition, which has created, among other institutions, the Commission of Truth and Special Jurisdiction for the Peace, the first being an extrajudicial institution, and the second being the court responsible for investigating and judging perpetrators. However, the Final Agreement currently lacks an identitarian force or collective national memory that is able to grant cohesion to its purpose of a stable and lasting peace, at the risk of going from an official narrative to an inconvenient heritage (Prats, 2005).

The Final Agreement, conceived as a document-monument, relates temporalities in a game of ruptures and continuities in peace and war in the digital or analogical public space, hence its characteristic of a national heritage inserted in an official and institutional historical narrative of national States. However, it is also a memory artifact that expresses like no other current artifact the collective traumas (Fried Amilivia, 2016) and the narratives of extreme violence, historical claims that dialogue, interconnect and add to one another in a single place, such as a frustrated land reform, which has as its main subject the farmers, Indigenous people and black people who inhabit colonization and refuge areas, the systematic assassination of the democratic left and of the social-democracy personified by the Patriot Union and the New Liberalism, the emergence of women in the public scenario of struggles for truth, justice, and non-repetition, and the recognition of the survivors and victims of the armed conflict as testimonies of a collective trauma that need to be processed.

In this symbolic exchange between archived memory and heritage as an active process, the Final Agreement (FA), declared as a cultural interest good and registered in the Memory of the Word Program, in the context of transition from war to peace that Colombia lives, transforms this document-monument into a system of relationships with other peace heritages and incorporated memories. Hence the importance of analyzing it in its trajectories and resonances, once it is part of the resources and cultural assets used by many ethnic and gender groups in their demands for memory, truth, and peace. Therefore, this work adopted, to understand peace heritage, a double dislocation that overcome the classic clash between subjectivism and materialism, or material and immaterial heritage, considering it both an experience-heritage and object-heritage.

The declaration of peace agreements as national and global heritage is not enough to preserve it in collective memory, although this is important for heritage and memory processes of peace, due to its scarcity and precariousness. It is hoped that heritage and memory policies, along with institutions of memory, archives, and museums, implement new strategies for its integral administration, which includes from its identification, research, and exposure to taking ownership of it in the daily lives of neighborhood, communities, and schools.

The strength of the Final Agreement in a transitional process with no significant rupture from war lies on the fact that, despite being incomplete, the Comprehensive System for Truth, Justice, Reparation, and Non-Reoccurrence Warranty and, especially, the national and international social movements of resistance to structural violence have incorporated the Agreement in their repertoires of collective action and in their legal actions. In this sense, what Le Goff defends about documents as monuments is fundamental once it is a product of power relations, involving a set of peace and war approaches by the Colombian society and activates memories and feelings that swing from rage, hate, and revenge just as to compassion, hope, and reconciliation in a time when Colombia is resisting to leave war aside, although also searching for peace building.

Traduzido pela agência Universo Traduções.

References

ARCHIVO GENERAL DE LA NACIÓN. Resolución n. 603, del 22 de agosto de 2018.

ARCHIVO GENERAL DE LA NACIÓN. Formulario de postulación Registro Memoria del Mundo de América Latina y el Caribe. Bogotá, 2017.

BANGUERO, H. La reestructuración unilateral del Acuerdo de Paz: a dos años de la firma del Teatro Colón. Cali: Sello Editorial Unicatólica, 2019.

CANDAU, J. Memorias y amnesias colectivas. Antropología de la memoria, p. 56-86, 2002.

CANDAU, J. Conflits de mémoire: pertinence d’une métaphore? In: BONNET, Véronique (éd.). Conflits de mémoire. Paris: Éditions Khartala, 2004.

CATELA, L. El mundo de los archivos. In: Los archivos de la represión: documentos, memoria y verdad. Madrid: Siglo XXI Editores, 2002.

COMISIÓN DE LA VERDAD (Colombia). Hay futuro si hay verdad: informe final de la Comisión para el esclarecimiento de la verdad, la convivencia y la no repetición. tomo 3. No matarás: relato histórico del conflicto armado interno en Colombia. Bogotá: Comisión de la Verdad, 2022.

CONGRESO DE COLOMBIA. Acto legislativo 2, de 11 de marzo de 2017. Por medio del cual se adiciona un artículo transitorio a la Constitución con el propósito de dar estabilidad y seguridad jurídica al acuerdo final para la terminación del conflicto y la construcción de una paz estable y duradera.

CORTE CONSTITUCIONAL DE COLOMBIA. 11 de octubre de 2017. Sentencia C-630/17.

DEPARTAMENTO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA (Dane) (2017). Encuesta nacional de lectura. 2017. Recuperado de https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/cultura/encuesta-nacional-de-lectura-enlec.

FRIED AMILIVIA, G. Trauma social, memoria colectiva y paradojas de las políticas de olvido en el Uruguay tras el terror de Estado (1973-1985): memoria generacional de la post-dictadura (1985-2015). Ilcea: Revue de l’Institut des Langues et cultures d’Europe, Amérique, Afrique, Asie et Australie, v. 26, p. 1-24, 2016.

GIRALDO LOPERA, M. L. Archivos, derechos humanos y memoria: una revisión de la literatura académica internacional. Revista Interamericana de Bibliotecología, v. 40, n. 2, SE-Investigaciones, p. 125-144, 1 maio 2017.

GUERRA, R. A. El papel del patrimonio cultural en el escenario de posconflicto en Colombia: paisaje, patrimonio cultural inmaterial y memoria para la construcción de paz. Revista Digital de Historia y Arqueología desde el Caribe Colombiano, v. 39, p. 116-141, 2019.

HALBWACHS, Maurice. Los marcos sociales de la memoria. Anthropos editorial, 2004.

HARRISON, R. Heritage: critical approaches. Routledge, 2013.

HERNÁNDEZ, Josep Ballart; TRESSERAS, Jordi Juan i. Gestión del patrimônio cultural. Capítulo 1: El Patrimonio Definido. 3. ed. Barcelona: Editorial Ariel, 2007.

HARTOG, F. Regímenes de historicidad: presentismo y experiencias del tiempo. Universidad Iberoamericana, 2007.

I MARTÍ, G. M. H. La memoria oscura: el patrimonio cultural y su sombra. In: CONGRESO INTERNACIONAL RESTAURAR LA MEMÓRIA, 6. La gestión del patrimonio: hacia un planteamiento sostenible. 31 oct.-2 nov. 2008, Valladolid, España. Anais... Junta de Castilla y León, 2010.

JELIN, E. Los trabajos de la memoria. Madrid, Siglo Veintiuno de España, 2002.

JELIN, E. Memoria. En: Diccionario de la memoria colectiva. Ricard Vinyes. España: Editorial Gedisa, 2018.

LÄHDESMÄKI, T.; THOMAS, S.; ZHU, Y. Politics of scale: new directions in critical heritage studies. v. 1.: Berghahn Books, 2019.

Le Goff, J. História e memória. 4. ed. Campinas: Unicamp, 1996.

LÉVY, Pierre. O que é virtual? São Paulo: Editora 34, 1996.

MOULY, C.; GIMÉNEZ, J. Oportunidades y desafíos del uso del patrimonio cultural inmaterial en la construcción de paz en el posconflicto: implicaciones para Colombia. Estudios Políticos, Medellín, n. 50, p. 281-302, 2017.

MOWLAC/UNESCO. Acta de la REUNIÓN DEL COMITÉ REGIONAL DE AMÉRICA LATINA Y EL CARIBE, 19. Programa Memoria del Mundo de Unesco, del 22 al 23 de octubre de 2018. IEEE – Communications Surveys and Tutorials, 2018. Disponível em: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/articleDetails.jsp?arnumber=6751036%0Awww.ijesrr.org%0Ahttp://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6114690/. Acesso em: feb. 2023.

NATHAN, I. The 1717 convention of Amsterdam according to French diplomatic archives. Quaestio Rossica, v. 6, n. 3, p. 675-684, 2018.

PAIMAN, Elison Antonio; ARAÚJO, H. M. M. Memórias outras, patrimônios outros e decolonialidades: contribuições teórico-metodológicas para o estudo de história da África e dos afrodescendentes e de história dos indígenas no Brasil. Arquivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, v. 26, n. 23, p. 1-24, jul. 2018.

PRATS, L. Concepto y gestión del patrimonio local. Cuadernos de Antropología Social, n. 21, p. 17-35, 2005. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/cas/n21/n21a02.pdf%20cultural.pdf.

PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA; FARC-EP. Acuerdo final para la terminación del conflicto y la construcción de una paz estable y duradera. 2016.

RUFER, M. Un fantasma en el museo: patrimonio, historia, silencio. In: JÓFRE CARINA, G. C. (ed.). Políticas patrimoniales y procesos de despojo y violencia en Latinoamérica. Buenos Aires: Unicen, 2022.

TAYLOR, D. Trauma, memoria y performance: un recorrido por Villa Grimaldi con Pedro Matta. Emisférica 7.2 – Detrás/después de la verdad, 2010.

VERA, J. P. Memorias emergentes: las consecuencias inesperadas de la Ley de Justicia y Paz en Colombia (2005-2011). Estudios Socio-Jurídicos, v. 17, n. 2, p. 13-44, 2015.

Received on March 31, 2023

Approved on June 21, 2023

Esta obra está licenciada com uma licença Creative Commons Atribuição 4.0 Internacional.